Hi everyone!

It's been a long time I've posted an update about this project because I've been working on the most labor intensive portion of it: the bodice! I've just finished it today so now I can share my process with you.

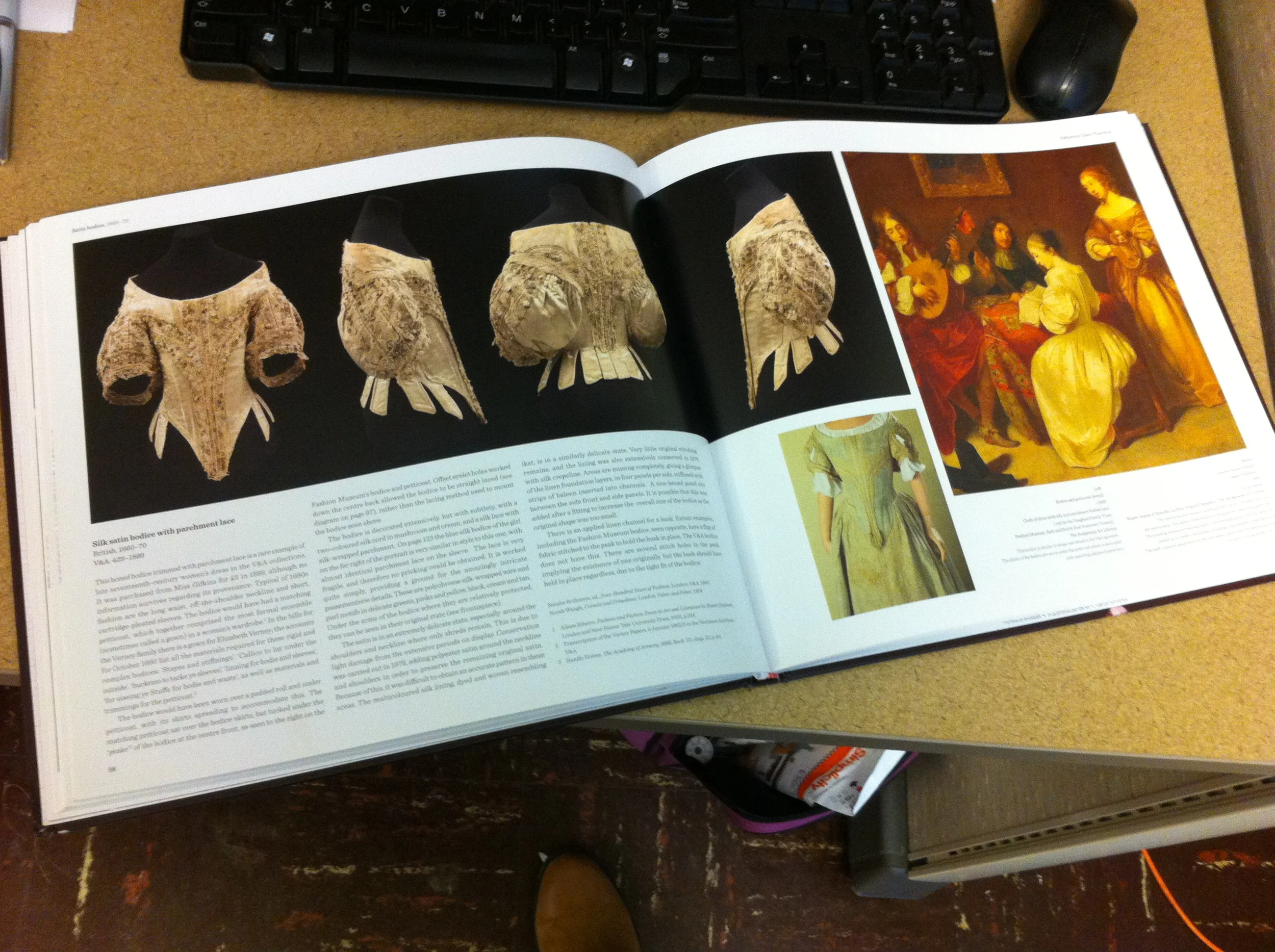

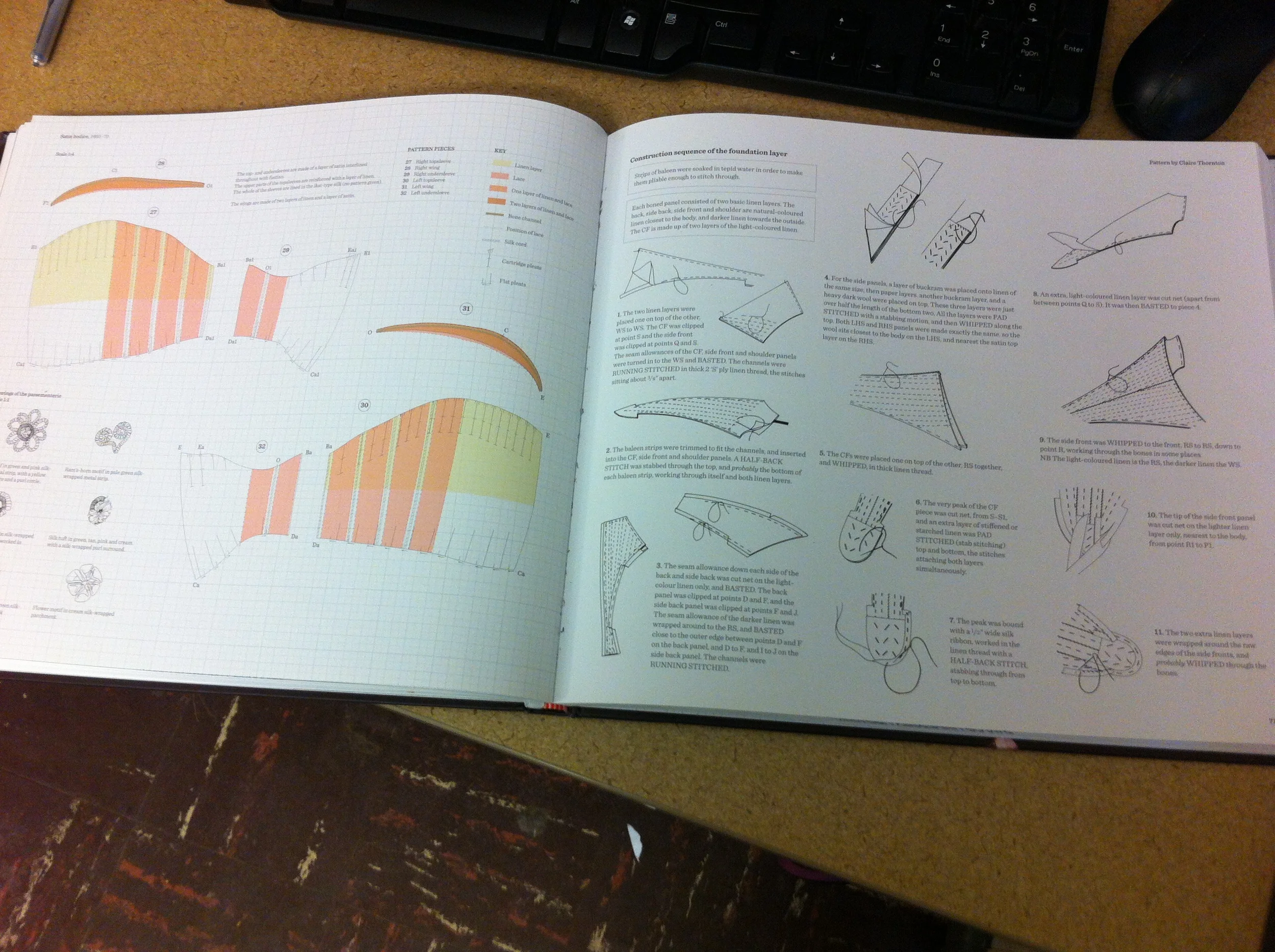

Now before I get into what I came up with I'd like to share my resources with you. There are a number of amazing books out there that detail historical costume patterns. Two of the best books on 17th century costume patterns are Jenny Tiramani and Susan North's (2013) Seventeenth Century Women's Dress Patterns: Book Two and Patterns of Fashion 1 (2005) by Janet Arnold. Both book authors use extant garments and developed very accurate patterns for garments from the 17th and 18th centuries. I relied heavily on Tiramani and North's (2013) book. The photos inside were gorgeous and the construction details were great!

While both books had patterns that could be scaled up, I decided to drape the bodice since I was working with the half scale form and some padded stick on arms. I used the books for ideas on laying out the boning, the pieces I needed, and how to shape my sleeves.

Now the extant pieces described in the book use a number of materials that were just not suitable for a display piece. After all this project is meant to be a learning tool for students to recognize 17th century dress. Details like internal support layers were not going to be visible to the students at the first glance. For example, the bodices in the 17th century were boned with whalebone. I don't know about you, but I'd have a tough time getting my hand on whalebone today! I opted for a cheaper alternative: plastic zip ties. Plastic zip ties are my go to for many costume bodices so I already had some I could use, and they provide ample support, especially in small places. I would not recommend them for a full scale version of this bodice or any corset that will be worn for long periods of time because over time they do warp with heat, but for photoshoot garments I think they're great.

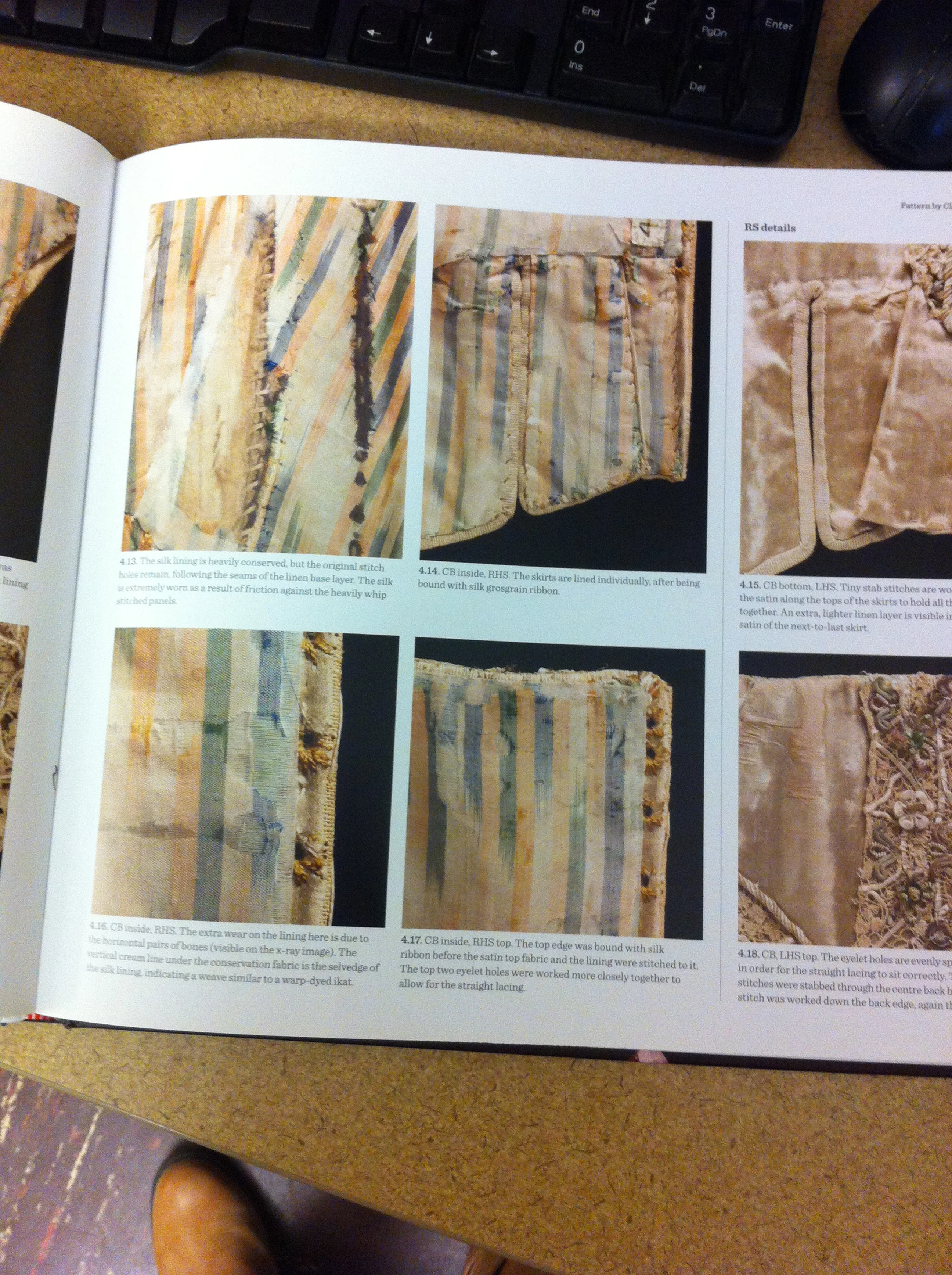

The downside to choosing the plastic zip ties is that you cannot sew through them. Several steps described in the Tiramani & North (2013) book require stab stitching through the bones (which one could theoretically do with whale bone) so I had to change some of the construction to deal with this. The largest change was the placement of the eyelet holes. In the case of the extant pieces the eyelet holes are very close to the edge of the garment and are sewn through the bones. I could not do this so I placed the eyelets in a small strip between two bones as if I were making a more modern steel boned corset.

The photo below is from the Bath Dress Flickr Gallery and it shows how the eyelets are sewn through the bones.

The extant pieces also involve a number of other small construction materials that were just not practical for my purpose. The Bath bodice and the bodice in the Tiramani & North (2013) book was underlined in layers upon layers of paper for stability. I could have theoretically done this, but I spoke to Dr. Pedersen and we both agreed that we'd like the option to be able to launder the piece if necessary and the paper would not have held up well in that case. We decided to omit it. For such a small scale garment there would be plenty of support with just the boning layer, the lining and the outer taffeta layer.

So once I had my materials I drafted the bodice, checked the fit, and then cut out the material for the boning layer. The boning layer is 100% linen. I sewed the boning channels with a hand sewn backstitch, turned each seam allowance to the inside, then whip stitched each piece together along the seam lines.

When I had the linen layer all sewn up I applied the outer layer by laying it flat over the bodice, turning under the seam allowances, and stab stitching it through all the layers. This follows the construction method outlined in the Tiramani and North book.

After this it came time to bind the tabs. Now on the Bath dress and in the Tiramani and North (2013) book they show the tabs bound with silk grosgrain ribbon before the lining is applied. The binding is only applied to the side tabs. In some places there is also binding along the neckline. I believe the binding for the neckline was mostly decorative so I decided to omit it and just bind the tabs. I did not have access to silk grosgrain ribbon and I find the ribbon offered at JoAnns to be kind of crunchy so I decided to just bind the tabs in the linen used for the interior boning layer.

As you can see my tabs are kind of funny shaped. They're part rounded and part square. I had some trouble with keeping the edges nicely shaped. I've certainly got some room for improvement. I'll talk more about my shortcomings later since I think they're important to address.

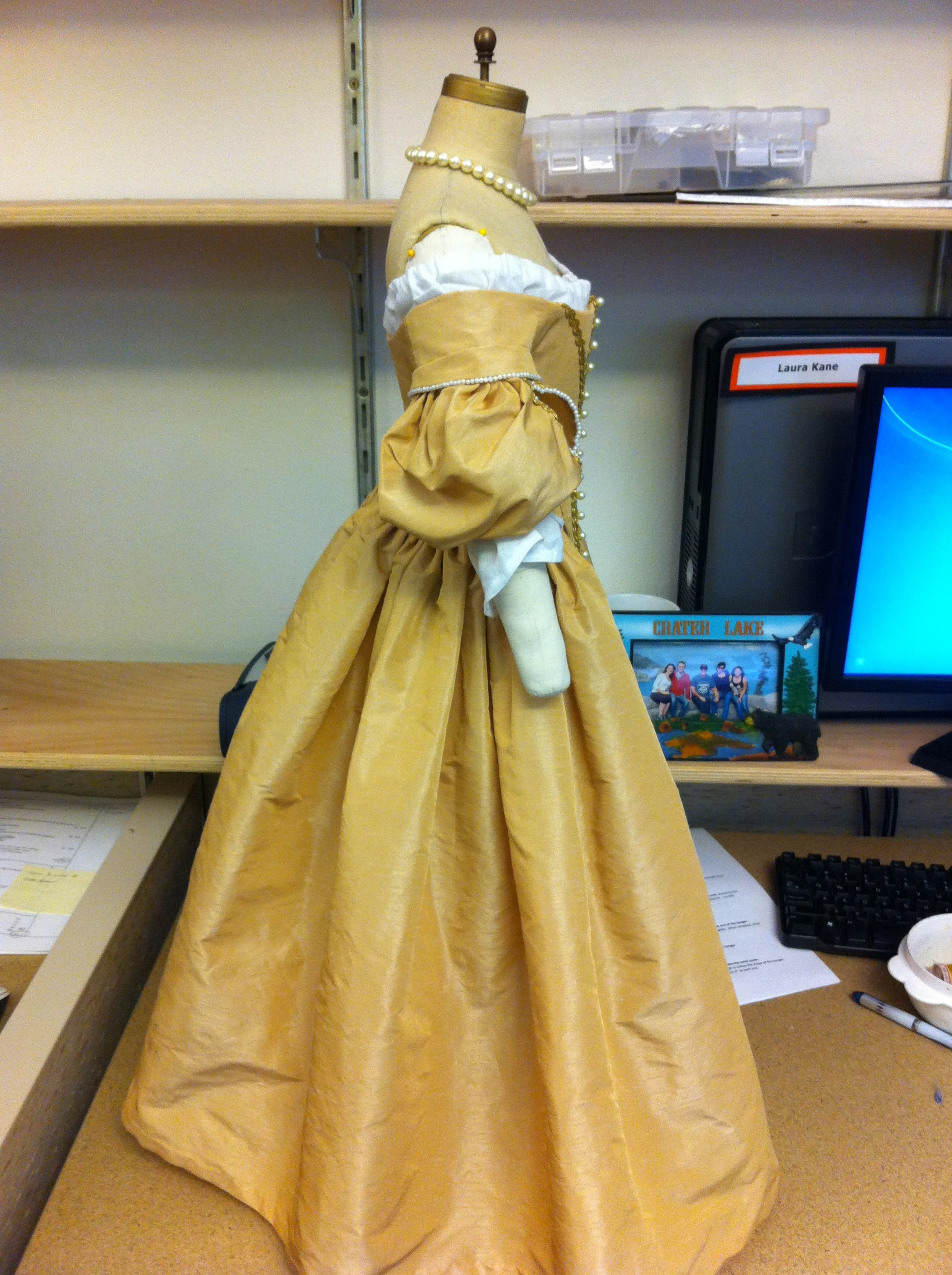

At this point I applied the decorations to the front of the bodice. In an attempt to keep this project inexpensive, I dug into my stash of metallic ribbons and trims. What I came up with were the only trims that looked appropriate and were similar colors. I also went back and looked at paintings and saw several paintings that used pearl decorations so I broke some of those out as well.

For the draping of the sleeve I went off of the pattern in the Tiramani and North (2013) book, made a mock up, made them even more full, lost my pattern piece, had to remake it, then finally ended up with something I liked. The construction of the sleeve is also a place where I deviated a bit from the historical methods. In the Bath bodice and in the Tiramani and North book the cartridge pleats by the top of the armseye are reinforced with paper and some added layers of muslin. The taffeta I was working with has a lot of body to it, and was poofing out quite a bit without any added layers. I also did not want to weigh down this poof with layers I felt weren't needed, so I omitted them.

Finally it came time to line the bodice. The lining was applied in a similar way to the out layer but instead of stab stitching through all layers, I placed one piece flat on top of the other and whip stitched the seam allowance to the piece next to it. I also used the lining construction detailed in the book, wherein each tab is lined individually. I used the same white handkerchief cotton I used for the chemise.

Once the piece was lined I applied hand sewn eyelets down the center back in a spiral lacing layout. That finished off the piece!

Now onto my thoughts of the finished piece and what I'd change. I'm constantly critiquing my own work looking for places to improve. The first thing I'd change is the shape of the front point. I simply made it too rounded and not pointy enough. I should have really exaggerated it. This time period is really defined by the super pointed jutting out front point and I could have gone to town!

Secondly I think I made the shoulder piece over the sleeve about a half an inch too wide. I think that piece is just too big. The proportion of that piece to the shoulder wing is off and it bothers the crap out of me.

Finally when I made the skirt I was using a different half scale form and when the waist tie closed the opening of the skirt in the back closed all the way. That dressform was just an extra in the sewing lab and not one of Dr. Pedersen's from the collection. The one from the collection ended up slightly larger so the skirt does not quite meet up together in the back. It's not super noticeable but still. Rawr.

Overall I'm really happy with it and I can't wait to see it all set up in a display case! The next step is putting together a more in depth research abstract and submitting it to Costume Society of America's next symposium! Wish me luck!

References:

Arnold, J. (2005). Patterns of fashion 1: Englishwomen's dresses & their construction c. 1660-1860. London: Macmillan.

Tiramani, J., & North, S. (Eds.). (2013). Seventeenth-century women's dress patterns: Book Two (Hbk. ed.). London: V & A Pub.